HOUSTON — The Texas economy has been protected unlike elsewhere in the country during some of the nation’s most devastating downturns.

When the financial market crashed in 2008 and sent the United States into a recession, high energy prices provided the Texas economy with a sort of cushion. After the entire country eventually suffered from the financial squeeze, the number of oil rigs operating in the nation’s top oil-producing state increased as the fracking revolution spurred an energy production boom in Texas.

“When energy prices are high, that’s good for the state coffers in Texas,” said Steven Beach, dean of the College of Business at the University of Texas Permian Basin. “But it’s a bit of a drag on the economy elsewhere outside of Texas.”

Now, as more people are out of work in the United States than ever before and the national economic calamity from the coronavirus outbreak has reached all corners of the country, business is back open in Texas. State officials have said they want the economy to roar back to the strength it had before the coronavirus. But unlike previous downturns, experts said this time the oil and gas industry, which recently saw oil prices dip into the negatives, might hold the state’s economy back.

Demand for oil has plummeted during the public health crisis because people have not been flying, commuting or traveling due to the coronavirus pandemic. It’s still not known when people’s behaviors and habits might return to what they were before the ongoing pandemic.

The country’s biggest oil companies have slashed budgets by billions, other companies have gone bankrupt, and what was once the world’s hottest oil field — the Permian Basin — is “so surreal, so quiet,” said Virginia Belew, regional services director at the Permian Basin Regional Planning Commission.

“We probably have to let go of energy as being the No. 1 industry in the long run,” Peter Rodriguez, dean of the Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University, said in an interview. “That primacy is no longer in the cards for Texas.”

The national job report announced Friday was grim, with 14.7% of Americans now unemployed, and it was evidence that the report for Texas to be released later this month will likely be bleak. Already, at least 1.8 million Texans have filed for unemployment in the seven weeks since Gov. Greg Abbott declared the coronavirus pandemic a statewide emergency.

In many Texas towns tightly tied to oil, from Houston to the Permian Basin, local government budgets depend on oil, and some officials in those areas hope the price for a barrel of oil will eventually return to — or even exceed — its roughly $60 cost in January.

“Word is that no one has ever seen it this drastic,” Jim O’Bryan, the top local official in Reagan County near Midland, said in an interview. “Hopefully it will be short lived. It’ll come back, it always has.”

Reagan County knows oil. It’s where the first well was drilled in the Permian Basin in 1923. And it was named after John Reagan, the first chairman of the state’s oil regulatory body — the Texas Railroad Commission — and an officer in the Confederate army. The county, like many others across the state, now faces an unprecedented downturn and historic job losses in the oil and gas sector.

The economy there, according to O’Bryan, the Reagan County judge, is going to take a serious hit as a result of the decimated demand for oil as the coronavirus has kept most of the world at home.

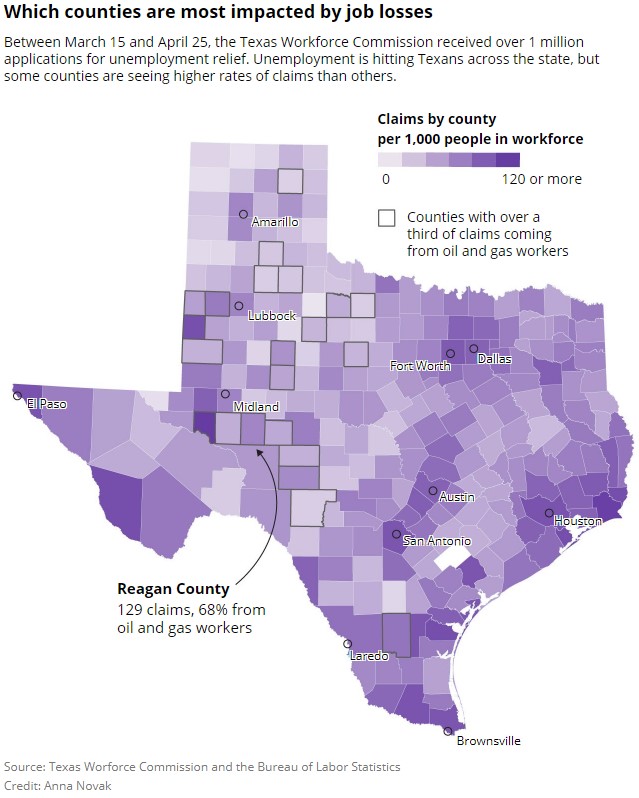

Along with the restaurant industry, oil and gas-related unemployment insurance claims filed with the state have risen rapidly. Oil and gas unemployment claims accounted for more than half of some counties’ claims filed between March 15 and April 25, a Texas Tribune review of state and federal data found.

In Reagan County, at least 68% of unemployment claims filed during that period came from the oil and gas sector, more than any other county in Texas, the review found.

“Many times during a downturn there will be a little boom somewhere else,” O’Bryan said. “But during this pandemic situation, there’s no place for people to go. There’s not other jobs.”

Those workers could have serious trouble finding new jobs in the oil and gas sector for at least the rest of 2020, according to analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

“Texas will likely underperform the U.S. this year, in part due to the downturn in energy,” Laila Assanie, senior economist at the bank, said in a video report this week.

While the oil and gas industry has been crushed, the economic destruction in Texas has hit a wide swath of sectors. After furloughs and layoffs that began in March and continue to this day, no part of the state’s economy has been spared.

Seeking unemployment benefits to ease the financial toll, millions of Texans have struggled to get through to the Texas Workforce Commission, resulting in jammed phone lines and confusing guidance from the state agency that could force some workers to choose between their health and a paycheck. Eventually, the agency changed its rules.

Claims keep coming in, though, and they aren’t expected to stop. For every county, the workforce commission breaks down unemployment insurance claims by sector. In Harris County, where Houston calls itself the energy capital of the world, the energy sector was not in the top five industries filing claims, the Tribune review found.

Analysts fear the worst of the financial fallout might not be over, but the data also shows the range of economic impact on the state’s major cities. The review found more than 5,000 unemployment insurance claims from Harris County were pegged to dentist offices; in Tarrant County, 3,271 claims were tied to automobile manufacturing; in El Paso County, 3827 claims were tied to clothing stores; and in Collin County, 1,737 claims were tied to department stores.

But high percentages of unemployment claims filed in many West Texas counties were related to oil and gas. In Yoakum County, 61% of claims filed were related to the industry; in Scurry County, 50% of claims were. And when communities that rely heavily on one industry see work in that sector dry up, there are suddenly a lot of out-of-work residents who don’t have money to support other businesses.

“Not to mention the supporting sectors — the restaurant or the machine shop or the auto parts store,” said Timothy Fitzgerald, an economics professor at Texas Tech University. “All those people are sort of part of the interconnected web.”

Disclosure: Rice University — Jones Graduate School of Business, Texas Tech University and the University of Texas Permian Basin have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

The Texas Tribune is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.