Democrats swept to victory in Virginia last year after campaigning on stricter gun control laws. Weeks later, the backlash began.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

Militia members arriving at a meeting in a Virginia suburb, ahead of a gun rally the following day

The Culpeper County 2A Facebook group had five rules.

Rule one was “Get Busy – Follow the Action Plan and take the necessary steps to protect our rights. Sharing memes isn’t enough. We need coordinated action.”

Rule two was “Do Not Give Up – We’re in the fight of our lives. Act accordingly. Never surrender.”

At some point in late January the rules changed, and rule two became “No racism”. But the basic purpose remained: Culpeper County 2A (the 2A stands for Second Amendment) was founded with the aim of resisting gun control bills working their way through the Virginia state legislature.

Similar groups are springing up across the state. Dozens of towns and counties are passing resolutions declaring themselves “second amendment sanctuaries” – a term borrowed from the “sanctuary cities” immigration movement of several years ago. The resolutions vary from county to county, but they broadly declare support for the second amendment and paint proposed state gun control laws as invalid.

Democrats won control of the Virginia House and Senate in November for the first time in 24 years, and they immediately proposed a raft of gun control measures from universal background checks to restrictions on high capacity magazines. The bills came as no surprise – the Democrats had campaigned heavily on gun control, backed by funding from activist groups which comprehensively outspent the National Rifle Association in its home state. Democratic candidates were responding to a growing clamour for gun control that began with the mass shooting of 32 people at Virginia Tech in 2007 and was amplified last year when a municipal worker slaughtered 12 people in Virginia Beach. When they won, the Democrats turned their proposals into bills and promised a wave of progressive legislation. Weeks later, the backlash began.

Nearly 200 Virginia municipalities have now passed second amendment sanctuary resolutions, turning the old Confederate capital – whose motto is “Don’t Tread on Me” – into a kind of frontline once again. The driving force behind the resolution in Culpeper County was Patrick Heelen, a local attorney who founded the Culpeper County 2A group and petitioned the county Board of Supervisors to hold a vote.

Heelen is a barrel-chested man, a little over six feet, who wears cowboy boots and has a long beard befitting his role as a captain in local Civil War battle re-enactments. He prefers the term “constitutional county” to second amendment sanctuary, because he believes the founding fathers intended to grant absolute gun rights to the population, in perpetuity.

“All eyes are on Virginia,” he told me. “America is watching what we do, how we conduct ourselves. America is watching to what extent we will be pushed around. America is watching to see if we are going to take a stand.”

I asked Heelen how far he and his fellow Culpeper County 2A members would go to defend their guns. “We are committed,” he said.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

Local attorney Patrick Heelen has been a vocal proponent of gun rights in Culpeper

At the first Board of Supervisors meeting in Culpeper, on a cold Tuesday morning in December, so many people came that the 180-capacity room overflowed into the hallway and clear into the parking lot. This was an unusual state of affairs for the Culpeper County Board of Supervisors.

“I’ve been on the board for 38 years and this was the biggest crowd I ever saw,” Bill Chase, the vice chairman, said afterwards. “It is the most fired up issue I’ve seen in all my years.”

Many at the meeting wore bright orange stickers reading “Guns save lives”, which are becoming familiar in parts of Virginia. Chase introduced the resolution, to a round of applause, and invited Culpeper County Sheriff Scott Jenkins to speak. Jenkins – the most senior officer in the county – quoted the constitution and the founding father of Virginia, Richard Henry Lee, and called the idea of restricting ownership of high-capacity 15-round magazines “insane”. He told the crowd that it wasn’t in fact the second amendment that gave gun rights to citizens, but God.

Jenkins also made an unexpected announcement that put Culpeper on the map in the sanctuaries movement: he said he would deputise anyone in the county who wanted, affording them the same broad gun rights as a sheriff’s deputy and allowing them to ignore new gun laws.

I met Jenkins later at the Culpeper County Sheriff’s office. “My statement was simply that I would choose to swear in hundreds or even thousands of our citizens as deputy sheriffs if need be, to allow them to possess weapons and push back on that overreach by our government,” he said.

He pointed out that Virginia already has lots of laws on the books that are not enforced. “We have laws against spitting on a public surface or sidewalk,” he said. “I cannot recall an officer enforcing that in the time I’ve been working.”

Some would argue that the gun control bills passing through the state legislature deal with more serious issues, like reducing access to the kinds of high-powered rifles that have been used to devastating effect in mass shootings, or making it easier to temporarily remove guns from those experiencing a mental health crisis.

But Sheriff Jenkins indicated that, were the bills to pass into law in the coming weeks, they would sit somewhere around spitting on a public surface in his list of priorities. “I guess if there are no other more important issues to focus on, maybe officers will focus on them,” he said.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

Sheriff Scott Jenkins in his patrol car. He has offered to deputise thousands of citizens

After Sheriff Jenkins had finished speaking at the Board of Supervisors meeting and a handful of residents had spoken in support of the resolution, the board adjourned ahead of a second meeting that night. At the evening meeting, which was similarly packed with supporters, one person stood to speak against the resolution.

As a young, sharply-dressed black man, Uzziah Harris stood out in several ways. He told the crowd the context of the Second Amendment was “clear in that it allowed for the keeping and bearing of arms in order to maintain a militia in times of emergency”.

“It never stated or specified as to how many or what type of firearm and it never said anything about lack of restriction regardless of mental or emotional capacity,” he said. “There currently isn’t a national emergency, nor does the military need supplements.”

Harris, a middle school English teacher, went on to cite cigarettes, alcohol, cannabis, cars and the internet as items generally and acceptably regulated. “So what is wrong with regulation of firearms?” he said.

At the end of the meeting, the Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to approve the resolution.

Harris has a detailed knowledge of parts of the constitution and can recite the second amendment, parsing its meaning as he goes. Like others in Culpeper opposed to this movement, he supports the second amendment. “Wholeheartedly,” he said.

“But there are limits that can be placed and should be placed on gun ownership. We should have background checks, we should make sure that people have the mental capacity to own guns. Hunting is one thing, protection of your families is another – but this influx of military weaponry, unlimited cartridges and rounds, how useful is that for hunting? How necessary is that for protection of your families?”

The proponents of the sanctuary movement are quick to dismiss hunting and family protection as reasons for defending gun rights, though. They are abundantly clear: the right to bear arms is about defence against a “tyrannical government” – a notion that dates back to the founding fathers.

“The thing is,” Harris said, “it doesn’t matter what you have in your stockpile, what chance do you have against the US military now? What chance do you have against drones?”

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

Uzziah Harris was the only person to stand against the resolution at a local meeting

The Saturday after the Board of Supervisors meeting, Culpeper County 2A and the local Republican Committee staged a rally at Culpeper’s Yowell Meadow Park, where local militia had mustered in 1770 to fight the British. About 500 Second Amendment supporters stood under grey skies and drizzle to hear Sheriff Jenkins and others speak about the sanctuary movement.

The gathering drew an impressive crowd for such a miserable day, but it was really only a warm up for a much bigger event. Jenkins, Heelen, and the other sanctuary supporters were all looking a week ahead to the annual Lobby Day rally in the state capital of Richmond, where as many as 50,000 people were expected to gather in the streets – many heavily armed – to protest against the Democratic gun control bills.

The rally was set for Monday 20 January. Over the weekend, people flooded into Virginia from nearby states and from as far away as Texas and California. President Trump weighed in on Twitter on Saturday, telling the nation: “Your 2nd Amendment is under very serious attack in the Great Commonwealth of Virginia. That’s what happens when you vote for Democrats, they will take your guns away.”

On the Sunday night before the rally, several state militia groups gathered for dinner at a community hall in a rural suburb about 30 miles outside of Richmond. Christian Yingling, the commander of the Pennsylvania Lightfoot Militia, helped organise the dinner. “We reached out to get a bunch of good reputable militias together to come stand with the people of Virginia,” he said.

Image copyright

Image copyright

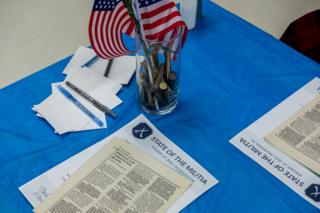

Joel Gunter

Christian Yingling of the Pennsylvania Lightfoot Militia.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

Local militia distributed leafets and used bullets as table decorations

Inside the community hall the crowd was mostly male and nearly entirely white. There were small arms holstered to people’s hips and tucked in the waistbands of jeans, and glasses of bullets as table decorations. There was a cross section of right and left-wing groups there – the Pennsylvania and South Carolina Lightfoot Militias sat alongside members of the John Brown Gun Club and a representative from the local Antifa chapter, which had announced days before that it would march on Monday alongside the pro-gun people. Unlike the deadly rally in nearby Charlottesville two years earlier, the politics of the Lobby Day rally were not right versus left.

The Virginia Citizens Defence League – a right-wing, pro-gun lobby group that organised the rally – led the meeting. The membership of the VCDL tripled in the wake of the Democratic midterm win, according to its president Philip Van Cleave – swelling from 8,000 to 24,000 members, and the group is now the driving force behind the Virginia sanctuaries movement. It had printed hundreds of large placards displaying a map of places that had passed resolutions – “91 counties / 12 cities / 22 towns”.

Greg Trojan, one of the founders of the VCDL, gave a speech singling out Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York and current Democratic presidential candidate, for funding gun control campaigns and candidates in the state. Bloomberg and George Soros – the Jewish financier who has become a fixture of right-wing conspiracy theories – came up several times. There is a perception that big-money Democrat donors bought the election and are forcing gun control on a state that doesn’t want it – allowing a dense urban population to dictate the law to the state’s rural conservative heartlands. VCDL promotional videos warn that Democrat-driven immigration is changing Virginia’s culture.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

Greg Trojan of the VCDL. “Don’t let the evil bastard win,” he said, of governor Ralph Northam

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

A handgun and spare magazines tucked in a waistband at a militia meeting in Virginia

The sanctuary movement is the conservative response – a pressure campaign directed at Richmond and backed by a lot of guns. “We’ve got people that were winning their seats by one and two percentage points, and now they’re looking at this,” Trojan said at the militia meetup, pointing to the sanctuaries map.

But unlike the sanctuary cities movement – which saw states oppose a federal immigration crackdown by the Trump administration – the sanctuary counties resolutions have no real legal force. “They are symbolic,” said Richard Schragger, a professor at the University of Virginia law school.

“Counties do not have any independent authority to create sanctuaries from state law,” he said. “State law applies equally to people in a sanctuary county and outside a sanctuary county.”

In Pennsylvania, the local Gun Owners of America (GOA) chapter is attempting to pass ordinances instead of resolutions, because they have some legal force. “It’s the difference between dating and marriage,” said Mary Luna, a GOA member from Pittsburgh.

The first such ordinance passed just last week, in Buffalo Township, Union County. It states that no official of the township shall “participate in any way in the enforcement of any unlawful act, as defined herein, regarding firearms.” An unlawful act is defined as “any federal or state law that restricts an individual’s constitutional right to keep and bear arms”. In other words, In Buffalo Township, it could soon be against the law to enforce the law.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

The streets of Richmond were awash with guns for the annual Lobby Day rally

Early on Monday 20 January, about 22,000 second amendment supporters spread into downtown Richmond. About 6,000 queued to enter a fenced off pen around the Capitol building. Guns were banned inside the pen but the streets around the Capitol were awash with them. There were small .38 revolvers tucked discreetly into waistbands and AR-15 assault rifles worn proudly across chests. There were old-fashioned hunting rifles. There were militiamen wearing body armour, helmets, ear defenders, rifles, sidearms and spare magazines; and there was a man in a dirty hoodie, cowboy hat and jeans who walked along the street with a shotgun swinging casually from his hand. There were at least two five-foot long, 50-calibre sniper rifles.

In among the arsenal of weaponry, there was a distinct sense of calm – possibly stemming from something like mutually assured destruction. “When people are around this many guns, they tend to act respectful,” Yingling said. He and his fellow militia leaders ran drills in the street, running up and down the lines and barking orders to their underlings, but most of the crowd just milled about chatting, sometimes chanting “USA”. John McGuire, a Republican Virginia House delegate, wandered through the crowd. “Evil does exist,” he said. “And when someone kicks down your door, if you have a gun you’re going to be glad you had a gun. If you don’t have a gun you’re going to wish you had a gun.”

At the end of the day, the organisers proclaimed the day’s peacefulness. Newspaper headlines said it was peaceful. None of the guns on display in downtown Richmond went off. But it was also hard to ignore the bristling potential for violence. The rally was intended – and successful – as a massive show of force. One large white flag with a picture of a rifle said, “COME AND TAKE IT”. All through the large crowd people carried the VCDL second amendment sanctuary placard, and some said that if defending their guns from new laws meant firing them at someone, they would.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

‘When someone kicks down your door, you’re going to be glad you had a gun.” said state delegate John McGuire

One inevitable outcome of a massive show of force is intimidation. The Coalition to Stop Gun Violence cancelled its own annual Richmond vigil, which had been due to take place directly after the rally, citing safety concerns and pointing out that many of its volunteers and staff were survivors of gun violence. And it is possible that terrible violence was only averted because the FBI arrested three members of a neo-Nazi group who were, allegedly, planning to travel to the rally and open fire into the crowd, in the hope of kickstarting a race war.

The VCDL has capitalised on the high profile of the Richmond rally to promote the sanctuaries movement. On Monday it put out a slick video with footage of the rally and a voiceover warning that mass immigration was threatening Virginia’s gun culture.

“As Virginians watch their Second Amendment rights erode, many are considering once-unthinkable alternatives,” the voiceover said. “Virginia will have to ask ourselves our most important question – what next?”

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

A gun rights activist defies Virginia’s no masking law at the Lobby Day rally

A month after the second amendment resolution passed in Culpeper County, Culpeper Town held its own meeting. Once again, there was only one dissenting speech, this time delivered jointly by Rich and Jacki Kaiser, a local couple who spent 50 years in the stained-glass business. The Kaisers live in a large, wisteria-covered corner house in Culpeper Town. They are not bullish or sanctimonious. They did not set out to be political, they said. “We just wanted our voices to be on the record,” Rich said. “We did not want to let the moment pass.”

Rich is partially deaf – a product of standing too close to heavy artillery guns in Vietnam. Unlike many of those brandishing AR-15s at the rally in Richmond, he has seen up-close what high-powered rifle bullets do to bodies. “Being in Vietnam gave me an understanding of what these guns really do,” he said. “And I knew when I came back to the United States that there was no need for guns here. We don’t need the same mentality at home that we had in a war.”

Jacki had her own reasons for supporting stricter gun control laws. She is spending her retirement years volunteering for a group that assists victims of domestic violence.

“It’s about the threat that they may be killed with a gun, and it’s an issue that mostly affects women,” she said. “So anything that saves someone’s life or makes a better life for their children strikes me to my heart. Because I know, but for the love of God, I could be them. I could be there.”

Image copyright

Image copyright

Joel Gunter

Rich and Jacki Kaiser stood against the resolution. “We just wanted our voices to be on the record,” Rich said.

At the Culpeper Town meeting, Rich and Jacki sat alongside people with guns holstered on their waistbands. They weren’t scared, they said, but they did feel intimidated. There is an undercurrent of violence that runs through the sanctuaries movement. Sometimes it is subtle, but sometimes it is overt – a guest at the militia dinner in Richmond, who did not want to be named, said that the authorities were welcome to take his guns but they would “get them bullets first”. Apparently this is a common refrain.

Most people I spoke to seemed to recognise that the resolutions were essentially symbolic. Few said they would abide by new gun control laws if they passed. Some said straightforwardly that if they lost the legal argument, the final arbiter would be their firearms.

“I think what you’re going to see next is a massive level of non-compliance,” said Yingling, the Pennsylvania militia leader. “And if they want to take that one step further to actual confiscation, there’s a very good possibility you will see armed rebellion in this country.”

I asked him if he saw himself on the frontline. “Yes,” he said, “absolutely”.

All pictures copyright